Researcher’s New Book Explores History of Cheap Stuff in America

or many Americans, time stuck in quarantine has been an opportunity to reassess and reorganize the space around them. Chances are, the arduous task began with a familiar refrain: Why do I have so much crap?

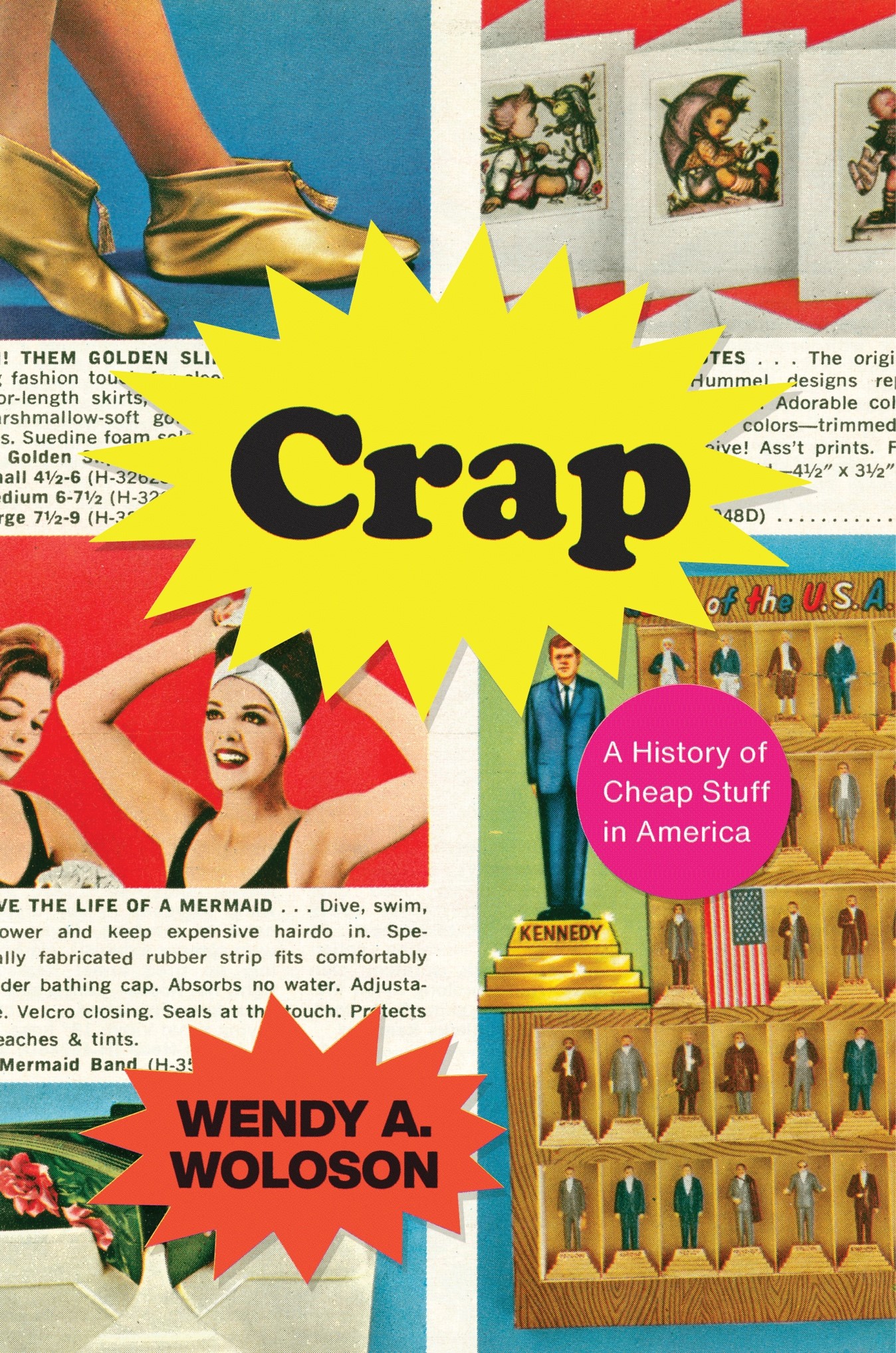

Photo provided by University of Chicago Press

It’s a common dilemma, and one that’s deeply woven into the fabric of American history, says Rutgers University–Camden researcher Wendy Woloson.

“Many people are surprised to learn that accumulating so much cheap stuff isn’t a modern problem, a condition of contemporary life,” explains the associate professor of history. “Rather, it dates back much further; to at least the early 19th century in America, if not earlier.”

Woloson, whose research specializes in the history of consumer culture and capitalism in America, explores the country’s long, love-hate relationship with inexpensive goods in her new book Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America, which was supported with a subvention grant from the Rutgers University Research Council.

“Crap is what you would call throwaway goods that are poorly made,” she says. “They are excessive, sometimes they don’t last very long or, in the case of gadgets, they don’t work very well. It is stuff we often don’t need, and sometimes don’t even want.”

While the fascination with cheap stuff is old, says Woloson, it has rarely been studied. She recalls that she had read countless research on material culture – “nice things, such as well-made furniture and art” – but scholars paid little attention to the run-of-the-mill artifacts that most people have all around them.

“Most average people don’t have masterpieces hanging in their homes, but we’re surrounded by this cheap stuff,” she says. “It intrigued me to learn more about why Americans have bought this stuff over time and how far back this fascination with cheap stuff goes.”

In her critically acclaimed account – the National Book Critics Circle has just named Crap a finalist for best 2020 book in the criticism category – Woloson breaks down different genres of crap and explains why people have been attracted to all kinds of cheap stuff for their own different reasons. For instance, she says, the consumer psychology behind the history of gadgets is different than the attraction to mass-produced collectibles.

With gadgets, she explains, people are drawn to the promise that they will perform labor for them very easily. Ad campaigns and sales “performers” use buzzwords such as “miraculously,” “like magic,” and “instantly” to appeal to consumers. People then buy gadgets not so much expecting that they will work well or that they will use them often, but to see these gadgets in action.

Wendy Woloson. Photo by Tim Tiebout.

“We want our labor to be lessened, but even more than that, we want to experience the magic of that instant transformation,” says Woloson, adding that today’s infomercials have their roots in the carnival barkers and traveling salespeople of the 19th century.

Meanwhile, people are drawn to mass-produced collectibles, she says, not only for their decorative appeal, but because they enable people to be collectors – and what is more, that they can hope that these objects might appreciate in value.

“So then the marketers of these mass-produced collectibles work hard to create appearances of value when these goods don’t have any of the properties that the fine arts and antiques actually have,” she says.

Woloson explains that Americans made a concerted choice in the mid-19th century to embrace a quickly democratizing consumer market. Goods were available at more accessible price points and were physically able to reach more people via peddlers, dry good stores, and, by 1870s, mail-order catalogues.

“In a lot of ways, this allowed people to participate in what I called ‘the goods life,’” says Woloson. “It allowed them to be consumers and to take advantage of what the market was offering.”

However, just because these goods flooded the market, explains the Rutgers–Camden history professor, that doesn’t mean people automatically snatched them up. Rather, people still needed reasons to buy them and to change their fundamental relationship with material artifacts.

At the time, she says, even wealthy people had few material possessions, which were well cared for, handed down over generations, and often served multiple purposes. An artisan, for example, might have used a worktable during the day for his work, it would become the kitchen table in the evening, and then folded out to become a bed at night.

Similarly, clothes were refashioned over time, taken apart and recut to serve different purposes, and passed down until the cloth could no longer be sewn into a new garment.

“Everything was well-made and you didn’t replace it,” says Woloson.

“You just took care of it.” Then, in the 19th century, she explains, there was a fundamental change in mentality. Americans decide that they no longer need to take care of these objects over time. It thus took out the burden of ownership.

“You no longer had to take care of something,” she says. “You could just toss it aside and buy something new.”

Woloson’s book explains how this historical, detached consumption and selling of cheap goods has impacted our lives today. This includes overseas manufacturing models that are built on exploited labor, as well as the adverse effects of having so many things made with non-biodegradable plastic enter the environment.

Woloson notes that buying cheap goods isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it has made people’s lives more comfortable and interesting. However, she hopes that people do think about the things they buy and why, and, just as importantly, the history behind it.

“It’s not my business to tell others what they should and shouldn’t buy,” she says. “However, I want them to understand how our consumer habits are part of a much larger history.”