Graduating Forensic Science Student Creates New Fingerprinting Powder

Kristen Smith had a problem.

The Rutgers University–Camden graduate student was conducting research in her forensics lab, following the recipe for a florescent-based fingerprint powder, when she realized that she couldn’t get a vital component in time to complete the project.

Smith now intends to patent her novel fingerprint powder formulation.

So she took matters into her own hands and considered what else could work. She ended up creating a novel formulation – used in the recovery of latent fingerprints, consisting of oils or sweat left from the fingertips or face – which she now intends to patent.

“It was the best mistake in the world,” says Smith, who is among the inaugural graduates of the master of science in forensic science program at Rutgers–Camden.

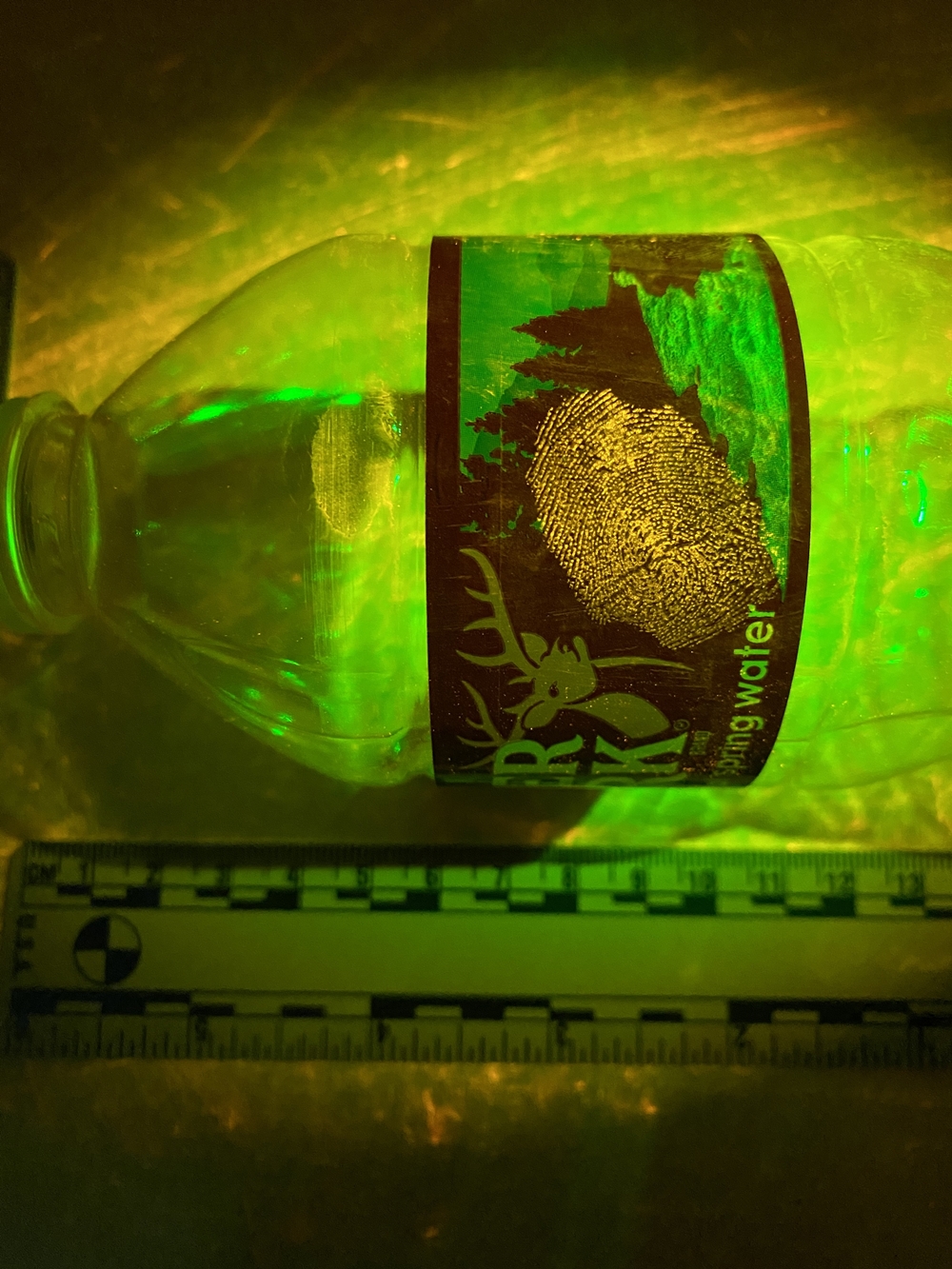

It turns out that the new powder might have a decided edge over the competition. She explains that the older version is florescent, which requires an alternative light source to see the fingerprints. However, since her powder is white-based, she was able to enhance, or bring out, the fingerprints without an added light source.

“That’s a big benefit that my powder now has over other florescent powders on the market,” says the Cherry Hill resident.

She adds that the powder’s ease of use also makes it a fantastic teaching tool – a theory she will put to the test this summer when she helps to train the Gloucester County Crime Scene Unit in fingerprinting.

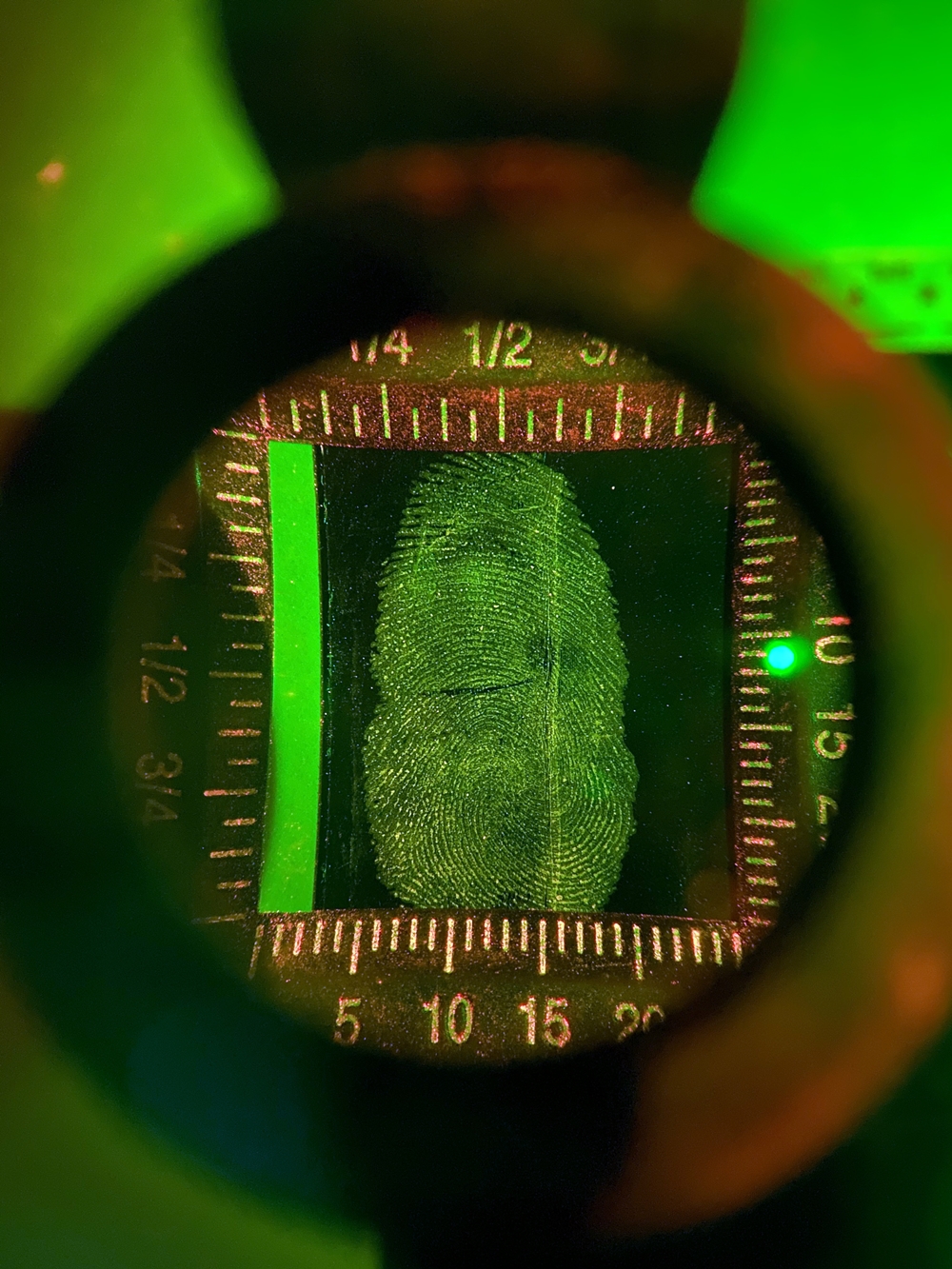

Smith notes that the powder recovers fingerprints with such extreme detail.

“I don’t mean to brag, but my powder works very well; it recovers fingerprints with such extreme detail,” she says.

Smith acknowledges that she had to put the patent application process on hold while she completed her senior capstone project. She notes, however, that Rutgers University has provided a patent attorney, who will soon work with her to complete the application process.

“Rutgers has been incredibly helpful,” says Smith, a Shrewsbury native. “Hopefully, within the next month or so, we will have all those details worked out.”

Smith’s chance discovery is just the latest stroke of serendipity that has launched her on a new career path that she once only dreamed of. Before she specialized in fingerprinting brushes and chemicals, she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in health and exercise science from the College of New Jersey in 2016 and taught nutrition and fitness classes for kids at the Trenton YMCA. She then decided to pursue her master’s degree in nutrition at Rutgers University.

Living in Cherry Hill, Smith took a class in chemistry principles at nearby Rutgers–Camden in spring 2018 to get the ball rolling. From day one, she says, she was “at home” on campus and in the classroom.

“I said to myself, ‘This is the school where I need to be,’” she recalls.

The graduating Rutgers–Camden student explains that the fingerprint powder’s ease of use also makes it a fantastic tool.

Smith struck up a friendship with the lab director, Mary Craig, who gave her a job prepping reagents for the chemistry courses and let her know about an exciting new forensics program that was in the works.

For Smith, it almost seemed too good to be true. She recalls that she had always wanted to work in forensics, with visions of being a crime scene investigator, since she was a little kid. Staying home sick from school meant a chance to binge-watch true crime shows and CSI the entire day.

“Part of it might have had to do with being an only child and having to be creative with my time and my mind,” she says.

Nonetheless, there was never an academic program around – that is, until the inception of Rutgers–Camden’s forensics program in fall 2019.

One of her first tasks in the forensics lab was preserving the remains of three human heads, housed for many years at a local museum. She cleaned the heads using beetles that subsist on human skin and, when they didn’t quite do their job, removed the skin by hand. Smith later made a presentation on the project at a bioarcheology conference.

She says that this type of experience in the lab reminded her of the importance of respecting human remains, and the way that forensic science can help survivors find answers – and perhaps even closure – during difficult times.

“I just want to do something to help people, and forensic science is an amazing way to do that,” she says. “People are in the darkest times of their life and you are helping them to make sense of it. It’s unfortunate to think about, but it’s so rewarding.”

Upon graduating, Smith aspires to work for the Camden County crime scene unit, specifically within their fingerprinting suite.

Smith acknowledges that she owes her burgeoning passion in forensics to Kimberlee Sue Moran, founding director of the forensics program, who espouses working for truth and justice.

“Especially with everything going on in our country right now, she really showed the importance of working for the truth and reaching justice in the right way,” she says. “I feel very motivated because of her.”

Upon graduating, Smith aspires to work for the Camden County crime scene unit, specifically within their fingerprinting suite. She praises the county for working transparently with the community. “They make it a point to let the community know that they are there to help,” she says. “I would love to work and be part of a team like that.”

One of her long-term goals – perhaps in retirement, she says – is to start a cadaver dog training facility employing rescue dogs. She would also like to work one day in the forthcoming Rutgers University Crime Lab Unit (RU-CLU), a Rutgers-based, multi-agency forensic lab, which will provide shared, streamlined services for Camden County and other New Jersey stakeholders.

Whatever her endeavors, Smith hopes to help other Rutgers–Camden students experience that same sense of community – and opportunity – on campus that she once had.

“I want to figure out how to give back to Rutgers–Camden in a way that they gave to me,” she says. “It will be part of my life’s mission to do that.”